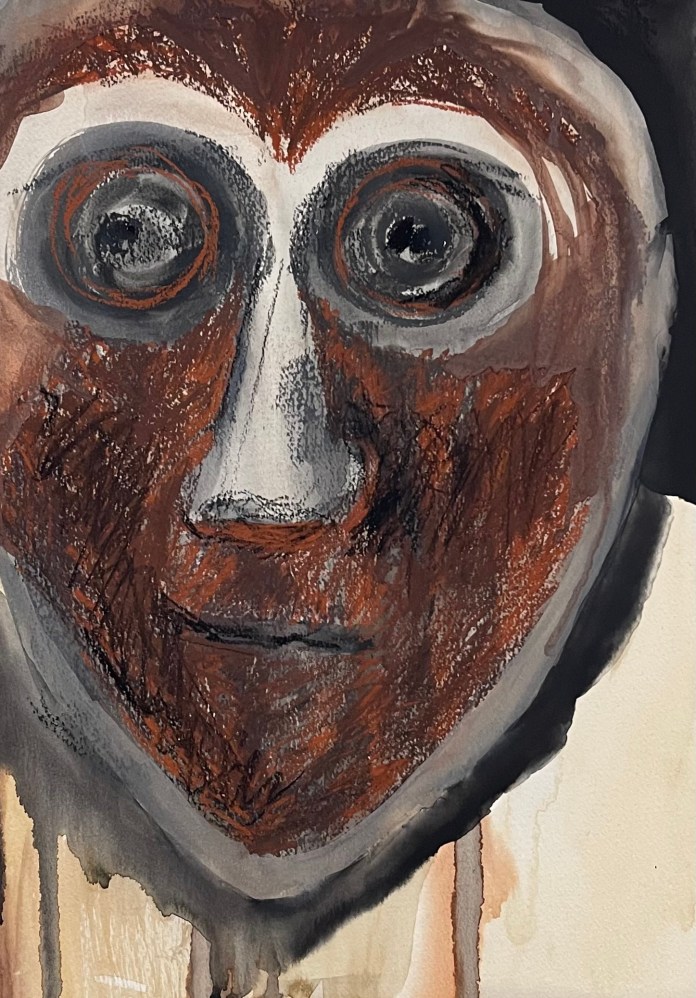

I made this weird piece of art, in mixed media including gouache, watercolour and oil pastel, inspired by reading an essay on the Sami writer and artist Johan Turi, in a book of essays and images: Sami Art and Aesthetics. Turi was alive from late nineteenth century to the 1930s, and his enterprise was to try and explain Sami-ness for outsiders, in order, as he believed, to help the Scandinavian governments of Sweden and Norway to understand the ways of the life of the Sami peoples. He believed that it was this understanding which would lead to the government implementing laws and structures which would help the Sami to flourish on their own terms.

In the essay by Seven Aamold it is explained that Turi’s visual art has been largely considered to belong within the label of primitive art, lacking in understanding of academic concepts such as perspective and so on. In the 1980s and 1990s, however, ideas about what primitive art constituted was challenged academically as colonial in perspective. The premise of Aamold’s essay is that a much richer reading of Turi’s work can be undertaken, an understanding that his “use of multiple viewpoints, from above, as upside-down images, or in detail…Turi added his motifs in rhythmic patterns, independent of any single perspective. The result is a strong impression of movement.” Aamold considers how Turi’s work reflects the unique epistemology of the Sami way of life.

Turi describes himself:

“I am a Sami who has (…) come to understand that the Swedish government wants to help us as much as it can, but they don’t get things right regarding our lives and conditions, because no Sami can explain to them exactly how things are. And this is the reason: when a Sami becomes closed up in a room, then he does not understand much of anything, because he cannot put his nose to the wind. His thoughts don’t flow because there are walls and his mind is closed in. (…) But when a Sami is on the high mountains, then he has quite a clear mind. And if there is a meeting place on some high mountain, then a Sami could make his own affairs quite plain.“

I don’t wish to romanticise, and I’m aware of Turi as a man, as a ‘hunter and a reindeer herder’, and so his concepts might not represent all Sami people, including Sami women. However, I find this idea interesting in artistic terms.

I chose his work ‘Mother and Child on a Sleigh’, a sketch he made on cardboard, which has no date. The staring face of the larger figure has been interpreted either as a mother and child of naturalistic origin, ie an illustration of Sami daily life, as the Virgin and Jesus from Christian tradition, or as an ulddat, which is a spiritual humanoid of Sami tradition. The small face, which I didn’t use in my work, might represent a child. Aamold’s preferred interpretation is of the sketch being the figures are of a mother and child from the ulddat realm. The ulddat are parallel spiritual beings, who guide human Sami but have independent lives, including children. Aamold’s interpretation of the face of the mother figure is interesting because he suggests how the face has a gaze ‘both inwardly and outwardly directed’. This interests me as in my interpretation of the figure, I decided to underpin it with a drawing I did a few years ago of the Italian writer Sylvia Federici. At the time I was researching the witch hunts in Europe, and read Fredric’s incredible book ‘Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation’. It’s a look at the witch hunts from an economic/political point of view, specifically its a history of the body in the transition to capitalism. giving a “panoramic account of the often horrific violence with which the unruly human material of pre-capitalist societies was transformed into a set of predictable and controllable mechanisms.” This strikes me as having a similar ring to Turi’s multi perspective way of perceiving and experiencing the world, which he was trying hopelessly to explain to the the governments, always hoping they would just finally understand if he could just explain properly.

When I painted the piece I wasn’t thinking about all of this too deeply, I just felt moved to use the ink drawing of Federici as an underpinning for it as I worked from Turi’s possible ulddat and child or virgin and child, whichever was inspiring him. Indeed we don’t need to ask the question as it strikes me as being a universally understood symbol. I realised later that what had interested me about Turi, apart from just responding to his art work, was his belief that if he just explained correctly then the figures in authority would understand, would have a flash of understanding, would experience a paradigm shift, which would make them not only accept Sami peoples as a ‘viable’ modern people, but would be inspired to help them to thrive on their own terms. He must have been convinced of this and seen evidence of it, or been reassured that he was on to something. It reminds me of the tendency of autistic people to overexplain things from their perspective, a tendency which is often reviled and has the opposite effect of irritating and making people stop listening. it reminds me also of David Graeber’s essay ‘Dead Zones of the Imagination: on violence, bureaucracy, and interpretive labor’ an essay which is central in my work and thinking, where he describes the tendency for ‘Violence’s capacity to allow arbitrary decisions, and thus to avoid the kind of debate, clarification, and renegotiation typical of more egalitarian social relations, is obviously what allows its victims to see procedures created on the basis of violence as stupid or unreasonable. One might say, those relying on the fear of force are not obliged to engage in a lot of interpretive labour, and thus, generally speaking, do not.’

It makes me think of Federici, being on the left politically, and an academic, and the oceans of words and ideas produced in this sphere, a whole universe of thought, dedicated to the deep analysis and interpretation of history, an effort to try to bend it towards the light, while the forces of politics and economics drive us ever further towards the dark days of authoritarianism and ecological despair. It’s as if we can’t seem to describe, or get through to, the trampling forces towards violence, no matter how hard we try…..

When I first began my deep interest in the Sami people and their art, I watched a film by Maja Hagarman and Claes Gabrielson, What measures to save a people? about Herman Lundburg who was a physician and professor who headed the world’s first state racial biology institute in Uppsala, Sweden from 1922-35. He was obsessed with the threat of racial mixing between Sami, Finns and Swedes and operated a years-long experiment in measuring and recording the ‘characteristics’ of Sami families, later serving as an advisor to the Nazis. That this was happening at the same time as Turi was trying so hard to explain the Sami world view through his art and writing speaks volumes.